Alexandra Fotaki

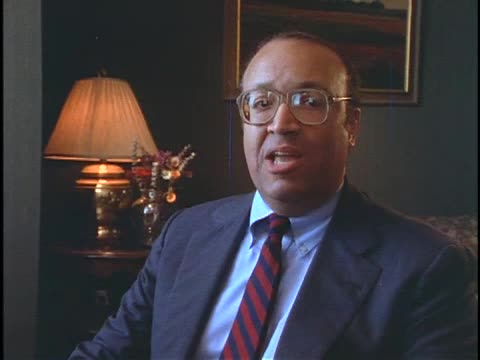

Adam Clayton Powell III is Director of the University of Southern California Election Cybersecurity Initiative and a keynote speaker in the hybrid international conference Cybersecuring Democracy which will take place in Athens on June 2, 2022 in cooperation with the Department of International and European Studies of the University of Piraeus, the University of Southern California Institute for Technology Enabled Higher Education (USC ITEHE) and the Council for International Relations (CfIR).

Cybersecurity and Democracy. How are they related?

Security is essential for democracy, as Greece discovered before anyone else. Cybersecurity is a present-day iteration of security, and it is no less essential than physical security has been for centuries. The enemies of democracy have seized on this, devising ever evolving cyber attacks to try to weaken democracies across the world and to try to shake faith in democracy itself.

Cyber security also has a role to play in defense? How important is this in the 21st century and what consequences could a hacker attack have?

Cybersecurity is essential for defense. Our team at USC monitors news media for a weekly cybersecurity news report that we email to thousands of subscribers, and we see accounts of malware, ransomware and other cyberattacks all over the world – and only some attacks are public.

We are only beginning to understand the damage a skilled bad actor can cause. Across the U.S., hospitals and schools have been hit with ransomware, where the institution’s networks are frozen and held hostage until the attacker has been paid. We may have just had a first in the U.S.: a 157-year-old college, Lincoln College, was forced to close its doors this month years because of a ransomware attack.

Given the Russian invasion of Ukraine, are you worried about a Russian cyberattack? Who could be the target and with what consequences?

Russian cyberattacks are a daily occurrence for us and have been for years. But by many measures, European countries have had more experience – and earlier experience – with cyberattacks from Russia than we have had. The U.S. has learned a great deal about defending against Russian attacks from the experience of European democracies. Right now we are watching the Ukraine defenses carefully, as Kyiv is deploying some of the most advanced techniques to defend against Moscow’s digital attacks.

Should Greece be worried about a cyberattack by Turkey in a period of tension?

We all must assume that any adversary is likely to employ cyberattacks as a weapon in times of tension – or even before. David Sanger, who covers intelligence for the New York Times, told me that more than 30 countries have hacked into the U.S. So I asked him for example of a country that we would not expect to do that; he quickly replied, “Bangladesh.” The reason: There is virtually no barrier to entry. Hacking is cheap and easy, at least at a low- to mid-level, and sometimes bad actors are just curious to see what they can learn by penetrating a digital network.

How important is cybersecurity for protecting democratic processes such as elections? In the age of the internet and social media, what is the role of misinformation and how can hackers alter the results?

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security uses an interesting measure: ROI. What is the “Return on Investment” for the bad actors? It is very difficult to change the result of a U.S. Presidential election: We have several thousand decentralized election districts, operating under different state and local laws, using different kinds of voting machines and paper ballots. The ROI is not favorable: it would require a major investment in a massive, sophisticated attack on at least hundreds of districts to try to change the outcome of the election. Instead, adversaries have discovered a much more favorable ROI: For a much lower investment, they can attack democracy itself, to try to lower confidence in elections and democratic governance and to create chaos.

Russia has been quite inventive in this area, developing new forms of attacks in each of our election cycles. In 2020, Russia used what we called “franchising,” employing American citizens working inside the U.S., many unaware of their employer, to spread disinformation on the Internet. In our elections this year, we expect to see more innovation from Russia and other enemies of democracy.

What are the safety valves?

Our lead cyber safety presenter, who will be in Athens speaking on June 2, begins his remarks in each of our programs by saying, “Everyone is a target, even you.” The way to remain safe is for everyone – everyone – to be vigilant. The bad actors only need to find one point of weakness. It could be one person with a weak email, or another person who has not turned on his mobile phone’s defenses. And the bad actors are trying, everywhere, all the time. We work with the Secretaries of State and Election Directors around the U.S., and one of them said in 2020, “We can see them trying to turn the doorknobs, but so far no one has gotten in.”

Cybersecurity is also important for the freedom of the Press and the Media?

Cyberattacks on U.S. media have been severe. One of the largest television companies, Sinclair, was hit with an attack, and weeks later, the telephones at some of its stations still did not work. The most dramatic attack on American journalists may have come on the day of our 2020 Presidential election. The Associated Press is our national media partner, and its President, Gary Pruitt, appeared on our first program in 2021. He said the AP was hit with “thousands” of “withering” “sophisticated” cyberattacks, most from Russia but also from other countries. They were not trying to change the result of the election. Instead, they tried to disable to AP computer system. According to Pruitt, if the AP went down, there would be no election returns, because the Associated Press is the sole source of election night information for newspapers, broadcasters and online media in the U.S. and around the world. Without the AP, it could take weeks for election returns to be reported.

What are the prospects for Greece to become a regional pole for the development of cybersecurity?

Greece is already a leader, ranked #1 in cybersecurity in a global survey by Estonia – the U.S. was #21! – so we want to have a true conversation next month, where we can learn from you as we share what we know. [See “National Cyber Security Index” at https://ncsi.ega.ee/ncsi-index/?order=rank]